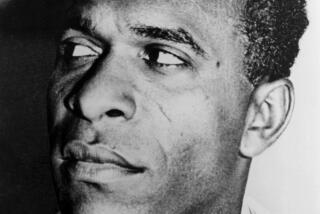

Sylvere Lotringer, intellectual who infused U.S. art circles with French theory, dies at 83

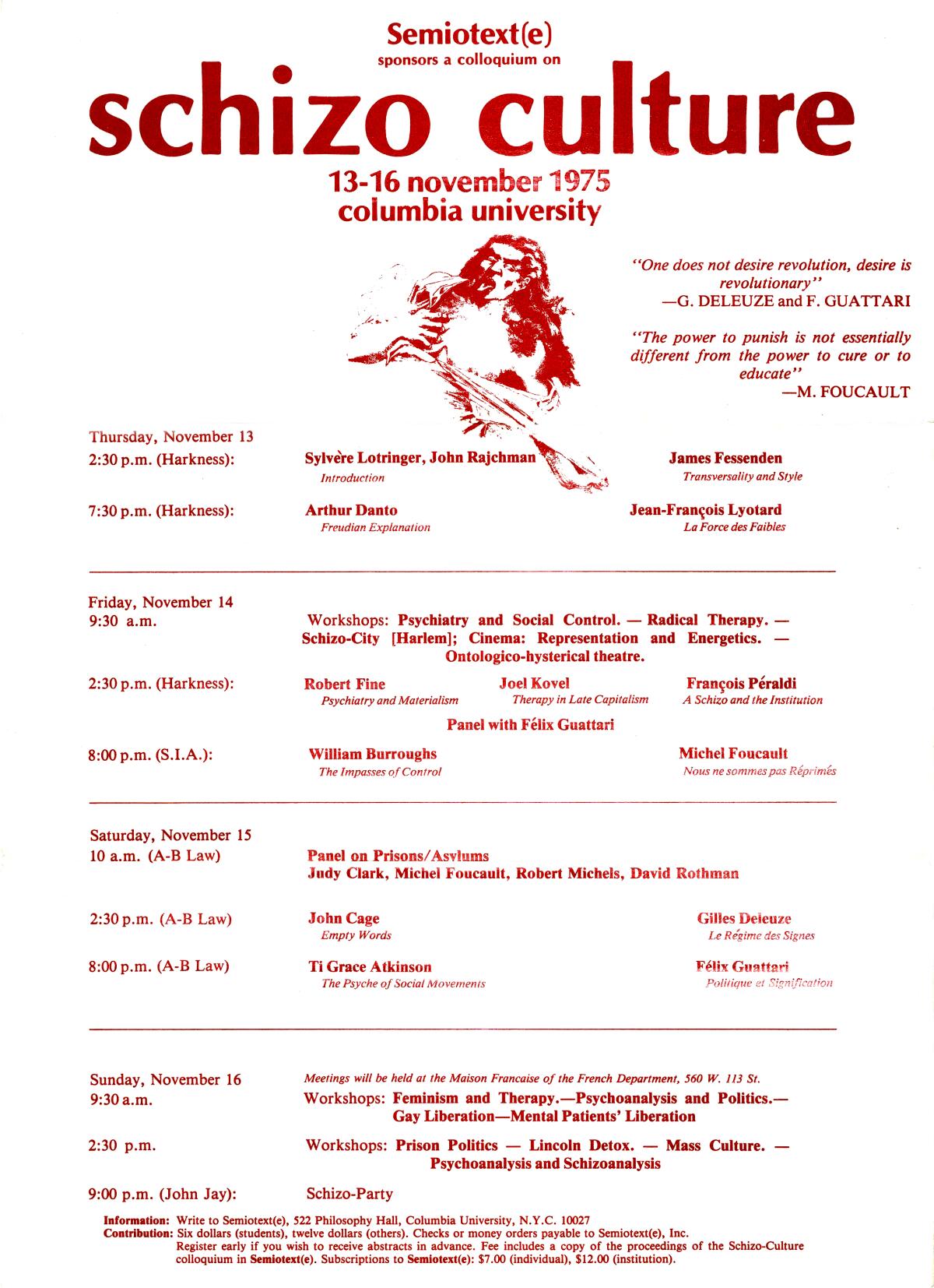

In November of 1975, a French literary scholar at Columbia University by the name of Sylvère Lotringer, along with a student, John Rajchman, organized a four-day colloquium that was intended to bring together a wave of avant-garde French theorists with various representatives of downtown New York City demimondes — presumably to discuss themes related to “prisons and madness.”

But “Schizo-Culture,” as the conference was titled, didn’t go quite as planned.

Early on, the narrow literary theme was scrapped in favor of what writer and researcher David Morris later described as “a delirious post-sixties intellectual free-for-all.” French philosopher Michel Foucault prepared a paper about repression; Gilles Deleuze was slated for a session about the interpretation of signs. Also on board was experimental composer John Cage, who was to deliver a chance-generated piece titled “Empty Words.”

It remained delightfully eggheaded until the Village Voice featured the colloquium as its “pick of the week” and more than 2,000 people descended on Columbia for the event. Fights broke out. Panelists attacked each other. During Foucault’s presentation, an attendee stood up and accused him of being a paid agent of the CIA. (He was not.) Félix Guattari, another French philosopher, impetuously canceled his own panel moments before it was set to start. “I am the chair of this panel and I abolish this panel,” he reportedly stated and then got up and left — as did a good portion of the audience.

At the center of it all was the affable Lotringer. In the 2014 book, “ Schizo Culture: The Book, The Event,” he recalled the chaos of the proceedings: “Foucault vented his furor and frustration at the conference. It was a scandal, he said; he had never seen a worse audience before; New Yorkers were horrible, the conference a sham.”

“Schizo Culture” may have seemed, in its moment, like little more than abject confusion. But it left a mark on intellectual culture in the United States. The event has been chronicled and re-chronicled, its happenings resuscitated at anniversary events. It also helped connect a generation of French philosophers — theorists who came of intellectual age in the wake of the events of May ’68, a season of protest that marked a cultural shift in France — with an artistic avant-garde of New York City. In addition to Cage, cut-up writer William Burroughs, experimental playwright Richard Foreman and underground filmmaker Jack Smith all attended the colloquium.

Lotringer served as critical connective tissue in myriad other ways, too. He founded the intellectual journal Semiotext(e), which later evolved into an ongoing publishing imprint of the same name. A lively intellectual hub, the company — which relocated to Los Angeles in the early 2000s — has published work by figures such as poet Eileen Myles, critic Gary Indiana and writer Chris Kraus.

Kraus has served as co-editor of the imprint since the 1990s and for a time was married to Lotringer. To the pop culture enthusiast, Lotringer’s name may therefore be more recognizable as Kraus’ husband from her groundbreaking 1997 work of autofiction, “ I Love Dick,” which explores her desires for another man, followed by desire more abstractly — all with Lotringer’s blessing.

When the book was made into a TV series by Joey Soloway in 2017, the part of Lotringer was played by Griffin Dunne.

Lotringer, a probing yet approachable scholar whose curiosity was sparked by a wide range of subjects — from French theory to graffiti — died of an undisclosed illness at his home in Ensenada, Mexico, on Monday. He was 83. He is survived by his wife, Iris Klein, and his daughter Mia Marano, along with Marano’s two children, Jonah and Nico Marano.

Awards

Kevin Bacon and Kathryn Hahn push television’s boundaries in ‘I Love Dick’

“I Love Dick” crams a lot of life into a double entendre.

Kraus remembers a brilliant scholar who was also an empathetic teacher. “He could meet people on their level and communicate this wealth of ideas to them,” she says via telephone. “So many people talk about how meeting Sylvère and hearing him made them change their lives. For him, all of this learning and all of this philosophy was a tool for living a more purposeful and meaningful life.”

Actor and writer Jim Fletcher, a founding member of the New York City Players theater company who first met Lotringer in the ‘80s, and who wrote poignantly about “Schizo-Culture” for a 2014 issue of Artforum, describes an “electrical” personality. “Conversing with him was always a thrill,” he says. “It wasn’t because of these massive articulations but because all of a sudden, whatever we were talking about became alive right in front of you — like touching a live wire.”

Sylvère Lotringer was born on Oct.15, 1938, in Paris, to Denise and Claude Lotringer, Jewish immigrants from Poland. His mother was trained as a pharmacist, but in France the family made a living as furriers, employing their humble apartment as an atelier. “They would cut furs on the living room table by day and use it as a bed for the children at night,” recalled Lotringer in a 2016 essay about his youth. “I can still feel the hair flying in my nose.”

It was a tenuous existence. The family kept rabbits in the building’s courtyard, one of which the young Lotringer took on as a favorite pet. But deprivation forced his parents to serve the animal for food. “Sylvère,” says Kraus, “refused to eat it.”

The Nazi occupation of France brought additional cruelties. Lotringer and his older sister, Yvonne, however, were among the lucky ones. They evaded the camps thanks to the kindness of their school’s headmistress, who through her connections with the Résistance secured fake identity papers. The pair were sent to live in the countryside as so-called “hidden children.”

“He was told, as a child, ‘You must never say your name or everyone in the house will be killed,’” says Kraus. For the duration of the war, Lotringer was “Serge Bonnard” and his sister Yvonne was “Hughette.” His parents survived in hiding as well.

Lotringer was not yet 7 years old when, in 1945, World War II came to an end and he was reunited with his parents. According to family lore, when the French flag was raised in their town’s square, Lotringer turned to his mother and said, “It’s so beautiful I want to die.”

World & Nation

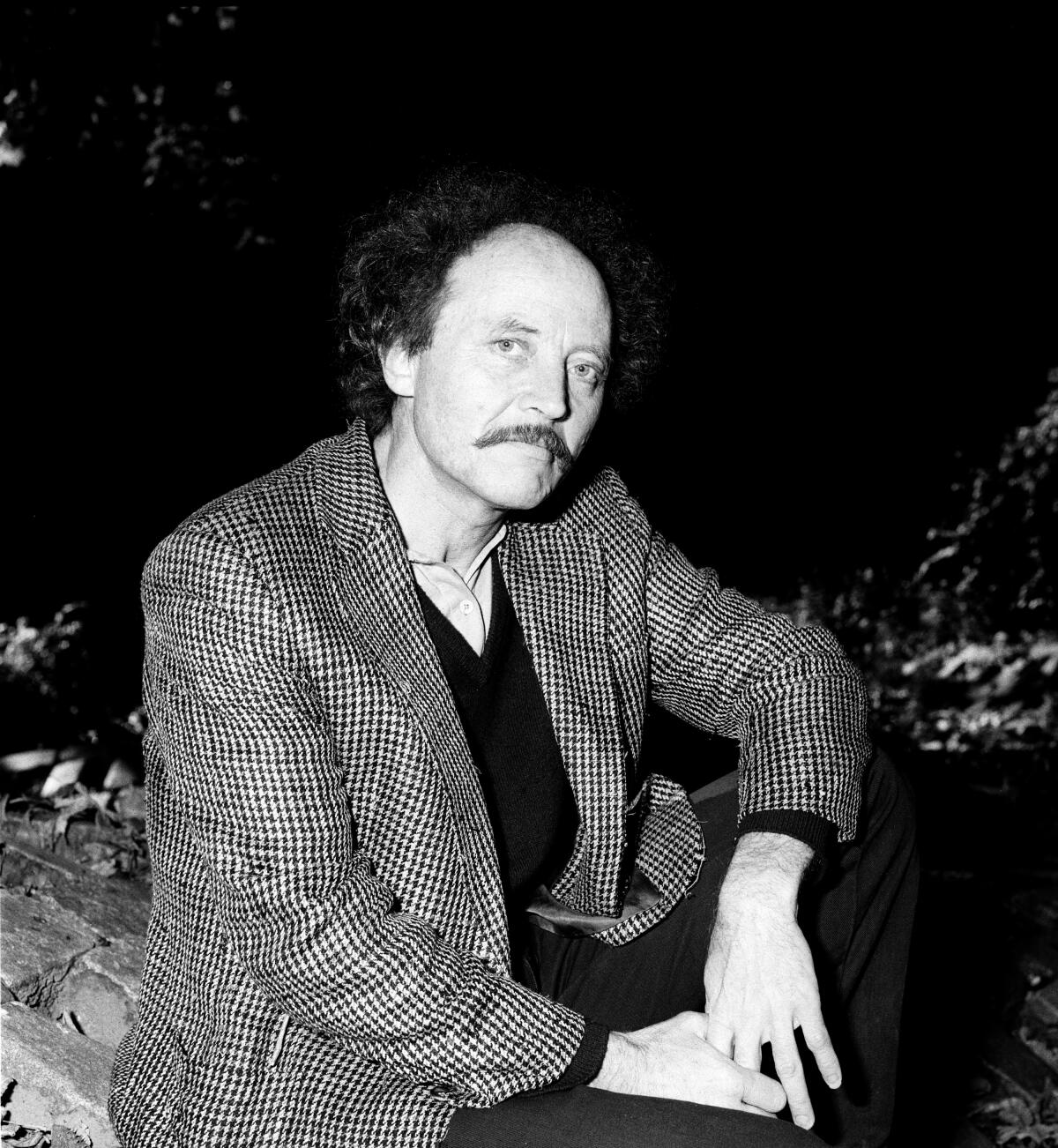

Jacques Derrida, 74; Intellectual Founded Controversial Deconstruction Movement

Jacques Derrida, the influential French thinker and writer who inspired admiration, vilification and utter bewilderment as the founder of the intellectual movement known as deconstruction, has died.

Marano says these early experiences shaped her father’s world view: “As someone who had been considered, as a child, an outsider, he was also really sympathetic throughout his life to people who had been marginalized.”

For a time, after the war, the family relocated to Israel. But with little economic opportunity there, they returned to France, where they ran a grocery store. It was one of his Paris schoolteachers who noticed Lotringer’s potential and helped him get into a prestigious secondary school, where he excelled.

This was followed by studies at the Sorbonne, where he co-founded the literary magazine L’Etrave. He went on to the École Pratique des Hautes Études, where he wrote his doctoral dissertation on Virginia Woolf — with supervision from Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann.

It was an early example of his commitment as a scholar: Lotringer took the extra step of traveling to London to interview the surviving members of the Bloomsbury Group. It was also an example of his politics. He had enrolled at the École Pratique to avoid serving in France’s war with Algeria.

“My education was a casualty of the war,” he told the Brooklyn Rail in 2006. “I got my PhD as a way of postponing the draft. Algeria was our Vietnam, and I wasn’t exactly keen on being sent there.”

After a succession of teaching jobs in Turkey, Australia and the U.S., he landed in New York in 1972, “hoping to catch up with the student rebellion at Columbia.” He would remain there — in the university’s French and comparative literature department — for more than three decades.

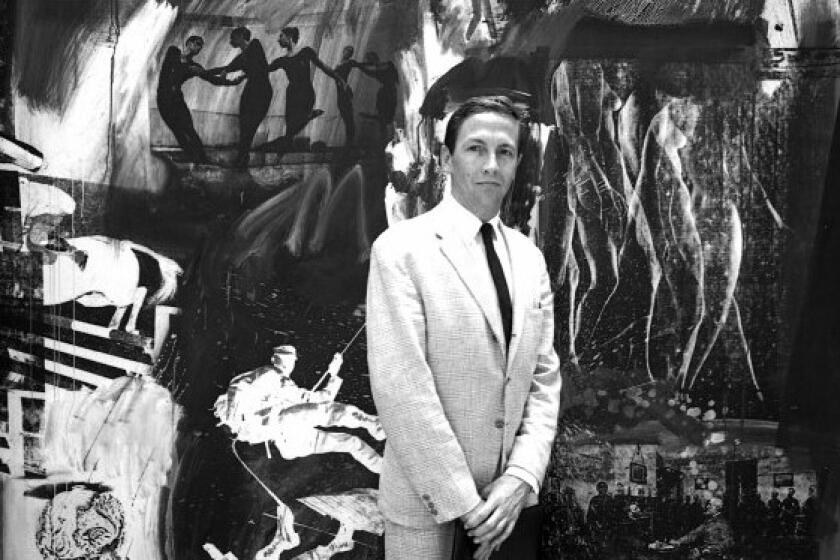

Two years later, he and his then-partner Susie Flato and grad student John Reichman established Semiotext(e), an intellectual journal that explored philosophy and politics as well as topics like polysexuality. A single issue might feature a text by Deleuze along with interviews of a female street gang from the Bronx. Text was not necessarily connected to images, many of which, as Fletcher once noted in an essay in Artforum, “had a pronounced s/m bent.”

The magazine remained in print until 1983, when Lotringer turned to publishing French theoreticians in translation under the Semiotext(e) name. Known as the “Foreign Agents” series, the little black books fit easily in a pocket. “Footnotes or other academic commentary were conspicuously absent,” Lotringer later wrote of the series. “Their place was in a the pockets of spiked leather jackets as much as on shelves.”

Books

‘Survival energy’: How COVID-19 and pregnancy fueled a fierce new book

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

He met Kraus in 1980 — a pairing that for many years was romantic but ultimately settled into being a lifelong intellectual collaboration.

Kraus was staging a play titled “Disparate Action/Desperate Action,” and she invited 10 people she considered famous to the show. A fan of Semiotext(e), she included Lotringer on the list. “He was the only one who came,” recalls Kraus. “ Susan Sontag didn’t.”

Their first affair was brief, but they bumped into each other three years later at a poetry reading and reignited their relationship; they married in 1988. Kraus joined Semiotext(e) in the 1990s. Noting that its publications were heavily male, she launched “Native Agents” series, which focused on literature by women.

Lotringer and Kraus separated in 2004 and divorced 10 years later. Kraus addressed their relationship in direct and indirect ways in a pair of novels, including “I Love Dick.”

Lotringer, she says, was “an unbelievably good sport” about appearing in her work and, later, in a TV series. “Sylvère always had a sense of humor and never took himself too seriously.”

By the early 2000s, Semiotext(e) had relocated to Los Angeles with artist Hedi El Kholti as co-editor. This collaboration has further expanded the areas explored by Semiotext(e) to include other subjects, such as queer theory.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, a humanities professor at Columbia who first met Lotringer in the ‘70s, said he embodied the spirit of that era.

“I thought of him as a primary text, not a commentator on radical theory, but as part of a way of thinking and doing which very much belonged to the ‘70s in France and radical New York and then California,” she said.

His influence, she said, was less rooted in his writing than in his way of life.

“He was not the kind of person who would necessarily leave an influence on scholarly thinking,” she added. Rather, he was “an example of how this kind of philosophy is also an act of the mind, of life, of how to actually live philosophically rather than simply think in a certain way.”

Books

Review: How a California acid trip made Michel Foucault a neoliberal

In “The Last Man Takes LSD,” two authors track Foucault’s late-in-life rightward turn, beginning with a hallucinogenic 1975 visit to Death Valley.

Lotringer was published extensively throughout his life, collaborating with French theorists Paul Virilio (“Pure War,” “Crepuscular Dawn,” “The Accident of Art”) and Jean Baudrillard (“Forget Foucault,” “Oublier Artaud,” “The Conspiracy of Art”). In 2007 he wrote “Overexposed: Perverting Perversions,” an update of Foucault’s “History of Sexuality” from 1976, and in 2001 he teamed up with Kraus for “Hatred of Capitalism: A Semiotext(e) Reader,” which features writing by many of the thinkers who influenced him.

El Kholti says Semiotext(e)’s long-running success — unusual for an imprint that is not supported by a university or a publishing conglomerate — speaks to Lotringer’s passion for living, but also the curiosity and the empathy he brought to learning.

“I think of doing something with integrity for that long, it has this influence in the culture,” he says. “It’s rare.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.